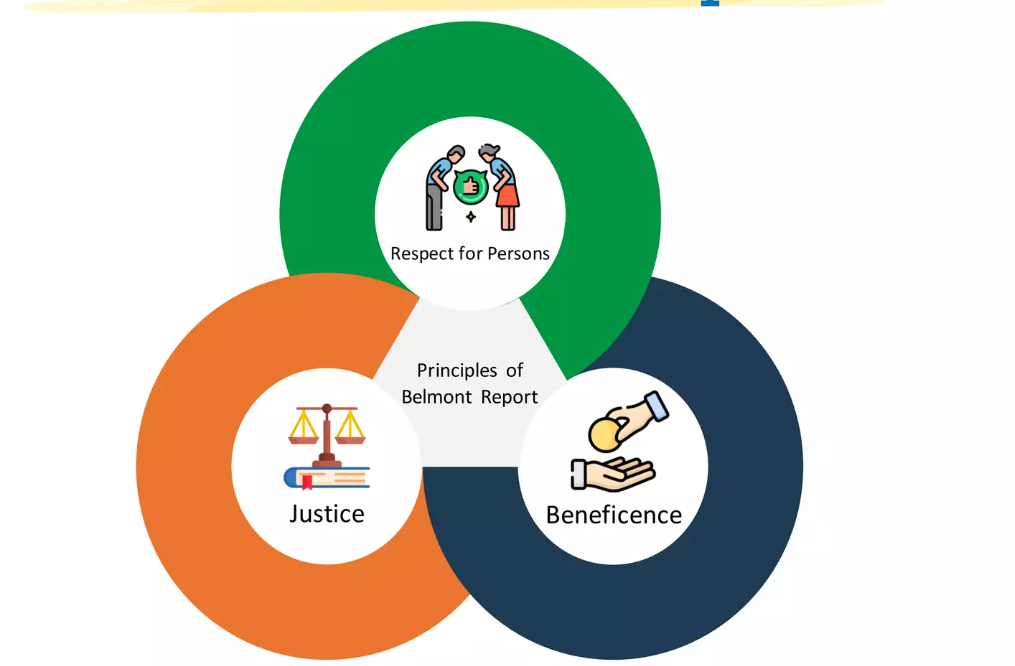

Over the decades, science has advanced by leaps and bounds. We now sequence genomes, run machine learning on massive datasets, and conduct social experiments online with minimal friction. Yet with that power comes a responsibility that sometimes gets lost amid methods, results, and “publish or perish.” The Belmont Principles, Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice, serve as enduring touchstones, reminding us that research is not a mere technical exercise but a human endeavor rooted in ethics and dignity.

The Belmont Report was born in a place of moral crisis. In the 1970s, public outrage over human-subjects abuses, most infamously, the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, forced the U.S. government to reckon with how research had betrayed trust (e.g., withholding treatment from Black men infected with syphilis) (Muscente, 2020). In response, Congress passed the National Research Act of 1974, which established a commission to define guiding ethical principles for research involving people (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services [HHS], 2023). Over nearly four years of deliberation, and an intensive four-day session at the Belmont Conference Center, the National Commission produced what became the Belmont Report (HHS, 2023).

What makes the Belmont Report remarkable is less its age and more its staying power. Rather than dictating every rule, it lays out three broad principles meant to inform decisions. The Report offers an “analytical framework” for confronting ethical dilemmas, rather than a rigid checklist (National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, 1979). As one scholar put it, the Report “aims to shape the moral viewpoint of those utilizing it within the research enterprise” (Saghai et al., 2024). Even today, its principles resonate in institutional review boards (IRBs), shaping how research is reviewed and regulated.

But times have changed: data flows freely, research is global, and technologies like AI and genomics introduce dynamics that the framers of Belmont could not have foreseen. So the question becomes: how do we bring these venerable principles alive in 21st-century research? This blog will explore how each Belmont principle can be translated into action today, what challenges arise in modern settings, and how we might adapt our moral compass without sacrificing integrity. Let us begin this journey by stepping into the first principle, Respect for Persons, and see how it must evolve in our current landscape.

2. Respect for Persons – From Informed Consent to Digital Autonomy

“Respect for Persons” is the Belmont principle that calls us to treat each human research participant as someone with dignity, worth, and agency, not merely as a data point. This principle has two core moral obligations: (1) to acknowledge autonomy, allowing individuals to make informed, free decisions; and (2) to protect those with diminished autonomy, such as children, people with cognitive impairments, or other vulnerable groups (HHS, 2023).

Informed Consent: The Classical Heart of Respect

At the center of this principle lies informed consent. That means participants should receive understandable information about what the study involves (purpose, procedures, risks, benefits, alternatives), have time to deliberate, ask questions, and agree voluntarily, free from coercion or undue influence (HHS, 2023). The Belmont Report itself makes clear that respect for persons demands a robust informed consent process.

In face-to-face, low-risk classical research, these requirements feel natural. But even here, problems can arise if consent documents are dense, full of legalese, or participants feel pressured (e.g., students participating in research run by their instructor). Incentives must not cross into undue influence. Recruitment materials and consent protocols need IRB oversight to ensure respect is preserved.

Challenges in the Digital Age: E-Consent, Literacy, and Autonomy

Once we move into digital and online research settings, informed consent becomes trickier, but its moral core doesn’t change.

- E-consent fatigue and low comprehension: Participants now often click through long consent forms online, sometimes skimming or ignoring details. Without a researcher present to explain, comprehension suffers (Xiao et al., 2023).

- Absence of dialogue and questions: The opportunity to ask clarifying questions may be limited or nonexistent in online settings, making a truly informed choice harder (Anabo et al., 2019).

- Assumed consent via usage or default opt-in: Some studies implicitly or explicitly rely on “agreement via use” (e.g., by simply using an app or site). That risks failing the voluntariness test.

- Digital literacy and access inequalities: Not everyone has the same ability to understand digital terms, privacy statements, or research jargon. Researchers must plan for varying literacy levels.

Scholars argue that consent models must evolve. Sedenberg and Hoffmann (2016) show that informed consent has historically been fluid, not static, and it must continue to adapt to modern data practices.

Beyond Traditional Consent: Toward Digital Autonomy

To honor respect for persons in a tech-inflected world, we need to think in terms of digital autonomy: giving participants real control over their data, how it will be used, and when they can withdraw.

- Layered or tiered consent: Present information in manageable chunks (e.g., “quick summary + more detail if desired”) so participants aren’t overwhelmed at once.

- Ongoing or dynamic consent models: Instead of one static consent, participants can revisit, adjust, or revoke consent as research evolves (especially in longitudinal or data-intensive projects).

- Interactive consent tools: Some experiments use chatbots or guided agents to walk participants through consent, allowing them to ask questions or pause (Xiao et al., 2023).

- Contextual consent for secondary data use: For example, mining social media data for health research might require special consent layers beyond platform terms of service (Norval & Henderson, 2017).

- Granular data permissions and revocability: Allow participants to consent to specific data uses (e.g., GPS, survey, biosamples) and withdraw particular permissions later.

- Transparency dashboards: Let participants see what data has been collected, how they are used, and who has accessed it.

Protecting the Vulnerable: Special Safeguards

Respect for Persons also insists on extra care when participants have limited capacity to consent, such as children, cognitively impaired individuals, and those in coercive environments. In digital settings, those vulnerabilities sometimes intensify. For example:

- Surrogate or guardian consent plus assent: One approach is having legally authorized representatives consent while the individual gives assent as far as possible.

- Simplified consent workflows: Use pictograms, plain language, multimedia, or audio to convey consent information to participants with limited literacy.

- Exclusion or extra monitoring: In some cases, excluding participants whose autonomy is too compromised or imposing stricter oversight may be ethical.

Gatekeeping Respect: Institutional and Researcher Roles

Ethical oversight via IRBs (or ethics review boards) must become more attuned to these digital challenges. Reviewers should ask:

- Is consent information clear, concise, and digestible for the actual participant population?

- Are mechanisms in place to let participants ask questions (e.g. chat, email)?

- Can participants withdraw participation or revoke data permissions easily?

- Has the protocol anticipated digital literacy disparities or consent fatigue?

Researchers, for their part, must adopt a mindset of participant partnership. Instead of pushing forms, they must think: “How can I help this person meaningfully understand and choose?” That shift in mindset helps us embody respect, not merely check a box.

3. Beneficence – Balancing Risk, Benefit, and Innovation

At its core, the Belmont principle of Beneficence reminds us that the purpose of research is not simply to discover new knowledge but to do so responsibly, by promoting good and avoiding unnecessary harm. This principle is rooted in two obligations: first, to do no harm, and second, to maximize possible benefits while minimizing possible harms (HHS, 1979). In practice, this principle extends far beyond avoiding physical injury; it challenges researchers to think critically about psychological distress, social stigma, data misuse, and even economic burdens that might arise from participation in research.

The Complexity of Risk–Benefit Assessment

Modern research, whether biomedical, behavioral, or digital, inevitably involves tradeoffs between potential benefit and potential harm. Determining what counts as “benefit” can be ambiguous: while participants may gain medical, educational, or social advantages, the broader good of the research may accrue to future populations. This temporal mismatch, immediate risk versus delayed benefit, makes ethical evaluation complex (Rid, 2022). Similarly, “harm” today encompasses not only physical injury but also breaches of confidentiality, algorithmic bias, or reputational damage in data-driven studies (National Institutes of Health, Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research [OBSSR], 2016).

Another key challenge lies in uncertainty. Researchers often, without direct engagement of IRBs, cannot fully predict adverse outcomes, especially in frontier areas like genetic manipulation or artificial intelligence. Probabilities and magnitudes of harm are sometimes speculative, leaving review boards to err on the side of caution. The ethical task, therefore, is not to eliminate risk, since no research is entirely risk-free, but to ensure that the risk is reasonable in relation to anticipated benefits and social value (National Ethics Advisory Committee [NEAC], 2019).

Practical Strategies and Safeguards

Applying beneficence in real-world research settings requires both methodological rigor and moral imagination. Ethical reflection must accompany every phase of a study, from design through dissemination, so that risks are anticipated, minimized, and continually reassessed.

- First, a rigorous study design is the foundation of beneficence. Poorly designed studies can expose participants to risk without the prospect of meaningful benefit. Using validated instruments, appropriate control groups, and pilot testing ensures that participant exposure yields useful, interpretable data. When uncertainty is high, staged or adaptive trial designs can reduce exposure by allowing early termination or modification once trends become clear. This approach reflects the moral responsibility to learn efficiently while protecting participants (Rid, 2022).

- Second, beneficence demands comprehensive risk mitigation planning. For known risks, researchers should implement detailed safety protocols, establish data-monitoring committees, and define stopping rules. For unforeseen harms, there must be systems for prompt reporting, participant follow-up, and ethical review. Importantly, beneficence also encompasses psychological and social dimensions. In social or digital research, this means preventing embarrassment, protecting confidentiality, and offering debriefing or counseling where distress may occur (OBSSR, 2016).

- Third, the principle calls for transparency and honesty in communication. Researchers must accurately convey uncertainties about risk and benefit, both in consent materials and public reporting. Overstating safety or downplaying potential downsides violates the moral trust that underpins voluntary participation. Informed consent must clearly express not only the purpose of the study but also its limits, especially when potential benefits are indirect or long-term.

- Fourth, beneficence today increasingly involves community engagement. Participants and affected communities should have a voice in defining what counts as harm and benefit. Their input can reveal cultural or contextual risks that researchers might overlook. For instance, in global health or AI research, communities may prioritize data sovereignty or equitable access to outcomes as key “benefits.” Participatory research frameworks, which invite stakeholders into study design and interpretation, exemplify beneficence in action (Anabo et al., 2019).

- Fifth, beneficence extends to ancillary obligations, such as providing follow-up care or ensuring post-trial access to effective interventions. Participants who contribute to scientific advancement should not be left without recourse when harms occur or when successful treatments emerge. Offering medical monitoring, compensation for injuries, or continued access to therapies demonstrates moral reciprocity, a recognition that beneficence does not end when data collection stops (NEAC, 2019).

- Finally, modern beneficence demands ethical foresight in technology research. In data-intensive or AI-driven studies, risks may involve privacy breaches or algorithmic discrimination. Researchers must integrate “ethics-by-design,” building systems that minimize bias, secure data, and maintain accountability. Ethical audits, model explainability, and transparency dashboards all serve as tools to embody beneficence in a digital world (Floridi & Cowls, 2022).

Beneficence is not a passive ideal but an ongoing discipline. It calls for vigilance as studies evolve, humility about what is unknown, and the courage to pause or alter course when risks outweigh benefits. As science advances into new territories, beneficence remains the principle that reminds us innovation must never come at the cost of human well-being.

4. Justice – Equity in the Distribution of Research Benefits and Burdens

If Respect for Persons is about honoring autonomy and Beneficence about promoting well-being, then Justice concerns fairness, who participates in research, who bears its risks, and who reaps its rewards. The Belmont Report defines justice as “fairness in distribution” (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 1979). That deceptively short phrase carries profound implications, especially in today’s globalized, data-driven research landscape.

The Moral Logic of Fairness

Historically, the call for justice arose from hard lessons. Before the 1970s, vulnerable groups, prisoners, racial minorities, the poor, and institutionalized people were often recruited for risky studies from which they did not benefit. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study (1932–1972) and the Willowbrook hepatitis trials (1956–1970) remain painful reminders of how easily social inequities can be magnified in the name of science (Reverby, 2009). Justice emerged as a corrective principle, insisting that research participation must not depend on social vulnerability or convenience.

At its core, justice requires equitable selection of subjects and equitable access to the benefits of knowledge. It demands that those who stand to gain from the outcomes also share proportionally in the burdens. The question is simple but pressing: Are the people taking the risks also the ones who stand to benefit?

Fair Participant Selection in Modern Research

In modern biomedical and social research, ensuring fairness begins with participant recruitment. Researchers must avoid exploiting groups that are easily accessible or less able to refuse participation, such as low-income patients or students seeking course credit (Emanuel et al., 2004). Instead, selection should be guided by scientific objectives and social value. For example, if a disease disproportionately affects older adults or minority communities, they should be adequately represented in studies of that disease.

Yet justice goes beyond inclusion; it also concerns exclusion. Overprotective rules can unintentionally deny potential benefits. For decades, women of childbearing potential were systematically excluded from clinical trials to “protect” them, leaving critical gaps in drug safety data (Liu & Mellen, 2021). Justice means balancing protection with equitable opportunity to benefit.

In global research, fairness must cross borders. Low- and middle-income countries often host clinical trials for products later priced out of their reach. Ethical review now demands commitments to post-trial access, ensuring communities that bear the risk can access resulting interventions (Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences [CIOMS], 2016). Without this, research risks repeating colonial patterns where knowledge and profit flow upward, and harm stays local.

Data Justice and Emerging Frontiers

As research increasingly moves online, data justice has become the new frontier. When personal or community data are collected, analyzed, or monetized without consent or benefit-sharing, digital inequality mirrors older exploitations (Dencik et al., 2019). Marginalized populations, often over-represented in surveillance data but under-represented in governance, bear privacy risks without a reciprocal advantage.

To promote justice in digital research, scholars suggest principles such as transparency, participation, and redistribution. Transparency means explaining how data are collected and used. Participation invites affected communities into decision-making about data governance. Redistribution ensures that data-driven benefits, such as predictive health tools, are not limited to wealthy institutions. Justice, in this sense, is about correcting the power asymmetries encoded in modern data systems.

From Principle to Practice

Achieving justice requires structural commitment. IRBs must scrutinize recruitment and benefit-sharing plans, asking:

- Are groups being chosen for convenience or for legitimate scientific reasons?

- Will the research outcome benefit the community involved?

- Have researchers planned for post-trial access or fair data use?

Community engagement is equally essential. Collaborative or participatory research models invite communities to co-design studies, set priorities, and interpret results. This shifts research from on communities to research with them (Cargo & Mercer, 2008). Justice then becomes not an abstract moral claim but a lived partnership.

The Broader Vision

Ultimately, justice in research extends beyond compliance. It asks us to see participants not merely as data sources but as moral equals whose welfare and dignity carry weight. Fairness cannot be reduced to demographic quotas or token consultation; it is a comprehensive, bespoke approach of a continuous process of evaluating who is included, who decides, and who benefits. As new frontiers emerge, from genomics to AI ethics, the Belmont principle of justice reminds us that ethical science is not only about what we study but also how we share its fruits.

5. Beyond the Belmont Report – Expanding Ethical Horizons

When the Belmont Report was released in 1979, it was revolutionary. For the first time, a U.S. commission codified a moral framework, Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice, that continues to guide how research involving human subjects is conducted. Yet more than four decades later, the scientific and social landscape has shifted beyond what its authors could have imagined. Artificial intelligence, genomic editing, globalized data collection, and participatory research models have expanded both the scope and complexity of human research. The Belmont principles remain essential, but they are no longer sufficient on their own. Today’s ethical frontier calls for new lenses that account for collective rights, cultural diversity, and the digital ecosystems shaping human life.

Recognizing the Belmont Report’s Limits

The Belmont framework was born in a specific historical and cultural moment, largely Western, biomedical, and individualistic. Its emphasis on autonomy reflects a U.S. liberal tradition of self-determination, which, while valuable, doesn’t always translate seamlessly across cultures or modern contexts (Nagai et al., 2022). In many Indigenous or collectivist societies, decisions about participation in research are made communally rather than individually. Likewise, data-intensive research, where algorithms scrape information from millions of users, blurs the boundary between “individual subjects” and collective data ecosystems (Leonelli, 2021). The Belmont principles tell us how to treat a participant sitting across the table, but not necessarily how to treat an algorithmic dataset representing a community.

Moreover, emerging technologies create novel kinds of harm. The Belmont authors could not have foreseen the privacy risks of genomic databases or the biases embedded in machine-learning systems. These issues require ethical tools that go beyond personal consent and physical risk, toward systemic fairness, accountability, and collective governance.

New Ethical Frameworks: CARE, FAIR, and Data Feminism

Several contemporary movements have sought to expand the Belmont vision. One of the most influential is the CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance, standing for Collective Benefit, Authority to Control, Responsibility, and Ethics (CARE) (Carroll et al., 2020). CARE reframes data not as an individual possession but as a community resource tied to identity, culture, and sovereignty. It insists that Indigenous peoples must determine how their data is used, shared, and benefit their communities. This represents a profound shift from autonomy to stewardship, extending beneficence and justice into the collective realm.

In parallel, the FAIR Data Principles, Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable, emerged from the open-science movement. While FAIR focuses more on technical standards than moral ones, when coupled with CARE, it creates a balanced vision: data can be open, but also governed responsibly (Wilkinson et al., 2016). Together, these frameworks illustrate how ethical thinking is evolving from protecting individual subjects to managing collective digital assets.

Another complementary paradigm, Data Feminism, challenges hidden power imbalances in how data are collected, classified, and interpreted. D’Ignazio and Klein (2020) argue that ethics should include attention to structural inequality, representation, and voice. By centering marginalized experiences, data feminism extends the Belmont principle of justice into questions of epistemic fairness, who gets to define knowledge, and whose data are valued.

Integrating Emerging Ethics into Practice

Moving beyond Belmont does not mean discarding it. Instead, it means layering new perspectives on top of enduring foundations. Researchers can integrate these expanded ethics through several practical shifts:

- From individual consent to participatory governance: Rather than one-time consent forms, research involving communities or digital ecosystems should adopt collective consent models and community advisory boards.

- From transparency to accountability: Beyond informing participants, researchers must demonstrate responsible follow-through, showing how data are stored, used, and eventually deleted or shared.

- From protection to empowerment: Instead of treating participants as potential victims, ethical practice can position them as co-creators of research design and beneficiaries of its outcomes.

- From Western universality to cultural plurality: Ethics committees and funding bodies must acknowledge that notions of autonomy, harm, and justice vary across cultures and contexts.

These steps turn the Belmont ideals into living principles that evolve with society. They also remind us that ethical progress is not achieved through regulation alone but through reflexivity, the willingness of researchers to question their assumptions and listen to the voices of those affected by their work.

A Living Ethical Ecosystem

The Belmont Report provided the moral scaffolding for 20th-century research. In the 21st century, that scaffold must stretch to encompass digital interdependence, global data flows, and environmental responsibility. Ethics now lives at the intersection of technology, culture, and community. Expanding the Belmont vision is not a rejection of its wisdom but an act of renewal, a recognition that moral progress, like science itself, depends on continual revision and humility.

6. Applying Belmont in Practice – Institutional and Researcher Responsibilities

The Belmont principles, Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice, were never meant to sit in policy binders. They were meant to be lived. Turning them from philosophical ideals into daily research habits depends on two central actors: institutions and individual researchers. Both share responsibility for ensuring that ethical reflection is not a procedural formality but a living part of scientific culture.

Institutions as Ethical Stewards

Research institutions, funding agencies, and ethics boards hold structural power to embed Belmont values in the systems that govern inquiry. Their first line of duty lies in oversight. Independent IRBs, or their equivalents worldwide, review study proposals to ensure that consent processes are fair, risks are minimized, and participant populations are chosen equitably. Yet true stewardship requires more than compliance. It calls for cultivating an organizational ethos that prizes integrity as much as innovation (Resnik, 2018). Institutions can promote this culture in several ways.

- Ethics education: Embedding research ethics across training programs ensures that new investigators understand both regulations and moral reasoning. Mandatory workshops, mentorship programs, and scenario-based discussions help internalize principles rather than memorize rules (Steneck & Bulger, 2007).

- Transparent governance: Clear communication between researchers and IRBs prevents adversarial relationships. Publicly available review criteria, data-sharing policies, and decision rationales promote trust.

- Continuous review: Ethics oversight should not end with IRB approval. Periodic monitoring, audits, and post-study debriefs keep beneficence and respect active throughout the project life cycle.

- Whistleblower and accountability systems: Institutions must provide safe channels for reporting ethical concerns without fear of retaliation.

Global collaborations also demand institutional IRB coordination. Universities partnering across borders should harmonize ethical standards, respecting local laws and cultural norms while maintaining Belmont’s spirit. This global dialogue helps prevent “ethics dumping”, the outsourcing of risky research to regions with weaker protections (Schroeder et al., 2018).

Researchers as Moral Agents

While institutions create frameworks, researchers enact ethics in practice. Every design choice, interview question, or data-handling decision is an ethical act. Responsible investigators do more than seek IRB approval; they reflect continuously on how their work affects human dignity and social justice.

Applying Belmont personally begins with respect, taking time to build trust, listening, and adapting to participant needs. It extends to beneficence, through meticulous planning to reduce harm, protect confidentiality, and communicate results honestly. And it culminates in justice, by ensuring that findings benefit those who contributed and that marginalized voices are not erased from scientific narratives.

Modern researchers must also navigate novel duties: protecting digital data, ensuring algorithmic fairness, and mitigating environmental and community impacts. Incorporating ethics-by-design tools, such as data-protection impact assessments, bias audits, and community consultations, turns moral reflection into routine practice (Floridi & Cowls, 2022). Importantly, ethical engagement should continue after publication: sharing results transparently, acknowledging contributors, and correcting errors promptly.

A Shared Responsibility

When institutions and researchers view ethics as a shared, iterative process, Belmont’s vision comes alive. Oversight without moral commitment becomes bureaucracy; moral conviction without structure becomes inconsistency. The most ethical research environments are those where every stakeholder, from administrator to graduate student, sees ethical reflection as part of doing good science. Belmont’s real legacy, then, is not a set of rules but a mindset: one that links discovery with responsibility, and progress with humanity.

Conclusion

More than 40 years after its publication, the Belmont Report continues to serve as the moral compass of human research. Its principles, Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice, remain timeless, not because they offer simple answers, but because they invite continuous reflection. In a world transformed by artificial intelligence, genomic engineering, and global data networks, the Belmont framework endures as a living guide, flexible enough to evolve, firm enough to remind us that every innovation touches human lives.

Ethical integrity is not the responsibility of regulators alone. It rests on a shared commitment among researchers, institutions, and participants. Researchers must act with humility and transparency; institutions must build cultures of accountability; and participants must be respected as co-creators in the search for knowledge. Together, they sustain a cycle of trust without which science loses its moral legitimacy.

At Beyond Bound IRB, we believe that ethical research should never feel like an obstacle course. The Belmont Principles, Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice, remain the foundation of every study we review and every researcher we guide. But ethics today demands more than compliance; it requires expertise and care in handling the process, where every project receives comprehensive, bespoke support and a clear path from submission to approval.

Our approach eliminates unnecessary delays. With no roadblocks, just support, our team ensures an efficient, stress-free service that leads to fast, confident approval. Through direct engagement with our clients, we simplify complexity, eliminate obstacles, and foster collaboration between researchers, institutions, and communities. From first draft to final review, you’ll experience comprehensive support from professionals who understand both regulatory precision and the human purpose behind your research.

Let’s advance ethical discovery, together. Partner with Beyond Bound IRB for ethics review and join IRB Heart to grow your ethical expertise. Because at the heart of every great study lies integrity, and we’re here to help you protect it.

References

Anabo, I. F., Elexpuru-Albizuri, I., & Villardón-Gallego, L. (2019). Revisiting the Belmont Report’s ethical principles in internet-mediated research: Perspectives from disciplinary associations in the social sciences. Ethics and Information Technology, 21(1), 137–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-018-9495-z

Cargo, M., & Mercer, S. L. (2008). The value and challenges of participatory research: Strengthening its practice. Annual Review of Public Health, 29(1), 325–350. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.091307.083824

Carroll, S. R., Garba, I., Figueroa-Rodríguez, O. L., Holbrook, J., Lovett, R., Materechera, S., Parsons, M., Raseroka, K., Rodriguez-Lonebear, D., Rowe, R., Sara, R., Walker, J. D., Anderson, J., & Hudson, M. (2020). The CARE principles for Indigenous data governance. Data Science Journal, 19(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.5334/dsj-2020-043

Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences [CIOMS]. (2016). International ethical guidelines for health-related research involving humans. Geneva: World Health Organization.

D’Ignazio, C., & Klein, L. F. (2020). Data feminism. MIT Press.

Dencik, L., Hintz, A., Redden, J., & Treré, E. (2019). Exploring data justice: Conceptions, applications and directions. Information, Communication & Society, 22(7), 873–881. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1606268

Emanuel, E. J., Wendler, D., Killen, J., & Grady, C. (2004). What makes clinical research in developing countries ethical? The benchmarks of ethical research. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 189(5), 930–937. https://doi.org/10.1086/381709

Floridi, L., & Cowls, J. (2022). A unified framework of five principles for AI in society. Harvard Data Science Review, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1162/99608f92.efc0f59a

Leonelli, S. (2021). Data governance: Ethical and legal considerations in the new digital research economy. Springer.

Liu, K. A., & Mellen, P. B. (2021). Women’s involvement in clinical trials: Historical perspective and future implications. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 109(6), 1439–1447. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.2115

Muscente, K. (2020, June 15). Ethics and the IRB: The history of the Belmont Report. Teachers College, Columbia University. https://www.tc.columbia.edu/institutional-review-board/irb-blog/2020/the-history-of-the-belmont-report/

Nagai, H., Nakazawa, E., & Akabayashi, A. (2022). The creation of the Belmont Report and its effect on ethical principles: A historical study. Monash Bioethics Review, 40(2), 123–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40592-022-00165-5

National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. (1979). The Belmont report: Ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research. U.S. Government Printing Office. https://www.videocast.nih.gov/pdf/ohrp_belmont_report.pdf

National Ethics Advisory Committee (NEAC). (2019). National ethical standards for health and disability research. Wellington, NZ: Ministry of Health. https://neac.health.govt.nz/national-ethical-standards/part-two/8-research-benefits-and-harms/

National Institutes of Health, Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (OBSSR). (2016). Ethical challenges in behavioral and social science research. NIH. https://obssr.od.nih.gov/sites/g/files/mnhszr296/files/Ethical-Challenges.pdf

Norval, C., & Henderson, T. (2017). Contextual Consent: Ethical mining of social media for health research. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/1701.07765

Pressbooks. (n.d.). Belmont Report: Respect for Persons – Protecting human research participants. In Ethical Principles & Guidelines for Research. https://pressbooks.usnh.edu/hrt1/chapter/belmont-report-respect-for-persons/

Resnik, D. B. (2018). The ethics of science: An introduction. Routledge.

Reverby, S. M. (2009). Examining Tuskegee: The infamous syphilis study and its legacy. University of North Carolina Press.

Rid, A. (2022). Risk–benefit evaluation and its role in research ethics. In A. Caplan (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of clinical research ethics (pp. 313–330). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195342920.013.0030

Saghai, Y., Emanuel, E. J., & Faden, R. R. (2024). The Belmont Report doesn’t need reform, our moral imagination does. Research Ethics, 20(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/17470161241235772

Schroeder, D., Cook, J., Hirsch, F., Fenet, S., & Muthuswamy, V. (2018). Ethics dumping: Case studies from North-South research collaborations. Springer.

Sedenberg, E., & Hoffmann, A. L. (2016). Recovering the history of informed consent for data science and Internet industry research ethics. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/1609.03266

Steneck, N. H., & Bulger, R. E. (2007). The history, purpose, and future of instruction in the responsible conduct of research. Academic Medicine, 82(9), 829–834. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31812f764c

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (1979). The Belmont Report: Ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/belmont-report/read-the-belmont-report/index.html

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2023). The Belmont Report: Ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/belmont-report/index.html

Wilkinson, M. D., Dumontier, M., Aalbersberg, I. J., Appleton, G., Axton, M., Baak, A., … Mons, B. (2016). The FAIR guiding principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data, 3, 160018. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18

Xiao, Z., Li, T. W., Karahalios, K., & Sundaram, H. (2023). Inform the uninformed: Improving online informed consent reading with an AI-powered chatbot. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2302.00832